Make it Hurt

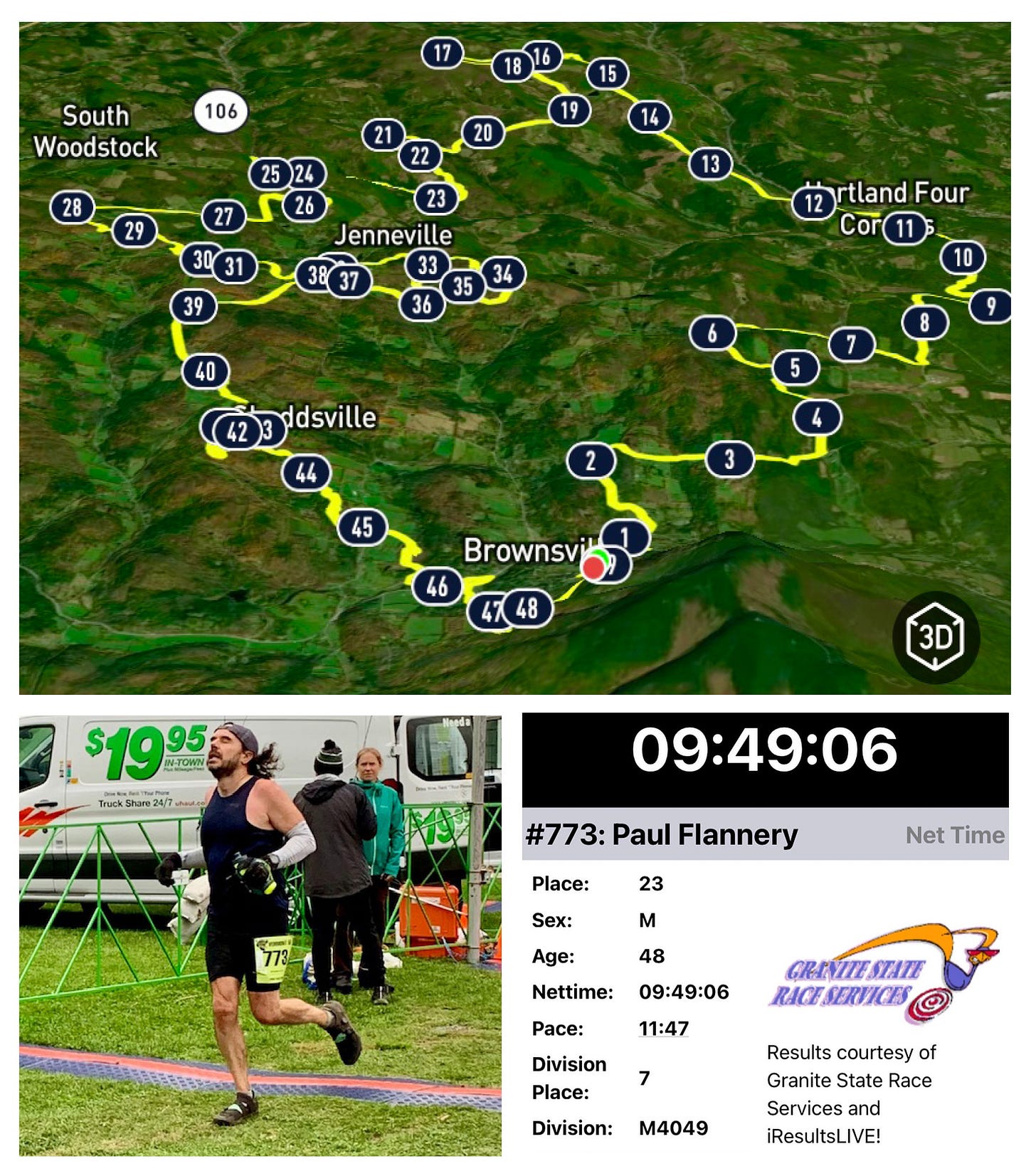

Pain and perseverance at the Vermont 50

In every race, no matter the distance, there is a moment of truth when everything is on the line. This moment has very little to do with time or place, even though both can be motivating factors. It has to do with what you have going on inside; how you view your performance, as well as yourself.

The moment arrives when the race becomes difficult and you are faced with a choice. Are you prepared to push forward no matter the cost, or will you give in mentally and surrender physically? This is when your race truly begins.

My Vermont 50 race began around Mile 37 at a small aid station known as Fallons. I had just come through one of the more taxing sections on the course, featuring six miles of endlessly twisting single track through the woods. On a normal day, this kind of running would be heaven. After six hours of racing, it was like a straight drop into hell.

Before entering the woods, I had been averaging a little more than 11 minutes per mile. That put me in a strong position to meet my primary goal of crossing the finish line in under 10 hours. Out in the unforgiving forest, alone and with few other runners in sight, my splits slowed to 14, 15, even 16 minutes per mile.

When I finally got to Fallons, my 10-hour cushion was gone and my spirits were dimming. It was eerily similar to how I felt during last year’s race, only that time my goal was to simply finish. This year, I was prepared to go deeper. With four miles of runnable downhill to the next aid station, the moment of truth was at hand.

“Make it hurt,” I told myself.

Now, I’ll be the first to admit this is not the most enlightened mantra. One might go so far as to call it masochistic, even potentially dangerous. In most cases, I wouldn’t argue. However, it was the right mantra for me at the time because I had spent the previous six months teaching myself how to suffer.

Much of that work was done unconsciously, part of the package when you’re training for an ultra. Some of it was done thoughtfully and deliberately. My goal throughout the whole process was to find out where my limits were, and push beyond them. This line of thinking was echoed in Coach Avery’s race plan:

“Alright, time to let it rip and really suffer. If things are hurting, you should be trying to see how much more you can make them hurt. You HAVE to keep pushing.”

Over the next two and a half hours, I ran as hard as I’ve ever run before. Throwing caution and good sense to the wind, I charged up rolling hills and blazed down descents leaving pieces of my soul along the course.

There was no looking back. No second guessing. This is what I came here to find out, and my purpose was clear. Make it hurt as much as possible, and then make it hurt some more.

Mile 41, Stones aid station

Arriving with another runner, I asked if I could balance on their shoulder to get a rock out of my shoe. There was no rock. My foot was simply inflamed. I put my shoe back on, and resolved not to think about it anymore.

Ahead lay more forest switchbacks, shorter in distance, but tighter and twistier than the previous ones. Up and down and round and around, it felt like we were running in circles. What madness was this, to be stuck in an infernal muddy maze, with the sky growing dark and light rain beginning to fall?

Sensing motivation beginning to wane, I returned to my mantra.

Make it hurt.

Toward the end of the switchbacks, I caught up with a small group of runners. Strong ones, about my age. We had about five miles to go and were suddenly locked in a race within the race. None of us would acknowledge this out loud, of course. There was no need, because each of us knew we would be fighting all the way to the finish.

We ran together for a stretch until we reached a clearing with a straight shot down a hill. That’s where I made my move. I took the descent with every shred of quad strength left in my body and opened up a small gap on the others.

Make it hurt.

Running hard along a river, I was back on sub-10 schedule heading into the final aid station. It was still a fine line. Any letup between here and the finish could prove costly in terms of time and finish. There was also the matter of a 450-foot climb waiting for us.

Mile 47: Johnson’s aid station.

As I rounded the corner turning into the aid station, my 9-year-old was there waiting for me. Fresh water bottle filled with hydration mix in hand, he expertly performed his crew duties like he’d done all day.

My wife and crew chief, Lena, ran such a well-oiled machine that I took less than 15 minutes total at aid stations throughout the race. A crucial time-saver, courtesy of an organizational savant and once-in-a-lifetime partner.

“You’re crushing it, dad!”

I was, in fact, crushing it. I was also hurting and prepared to make it hurt even more to get in under 10 hours. An admittedly arbitrary number of no consequence to anyone else, it represented everything I was trying to accomplish. At that moment, 10 hours was the only thing that mattered.

Heading up the final climb, knowing its steep grade is a momentum killer, determined not to break. Glancing back, seeing two other runners just a quarter mile behind. Maybe less. Grizzled vets, both of them. If they pass me it won’t be because I let up.

Make it hurt.

After finishing the climb, I headed back into the woods with a little less than two miles left. The sky had grown so dark, I could have really used a headlamp. Running on pure primal energy, pushing and churning, going so far beyond my limits that nothing would be left to chance. Not the time, nor the place, but most importantly, there would be nothing for me to regret about this day.

Make it hurt.

Out of the woods and flying down the final descent with about a third of a mile of straight drop until the finish line, letting grit and gravity take me home.

MAKE IT HURT, PAUL!

I’m saying this out loud as I pass spectators gathered on the hill. Their warm smiles and hearty cheering turning to mild concern by the sight of this crazed maniac barreling past them at breakneck speed. As I approach the finish line, I glance down at my watch and see that I’ve been running a 7-minute pace.

The other two runners come across the line roughly a minute later. None of us quit. Each of us pushed ourselves to the brink. We shook hands with respect and gratitude for bringing the competitive beast out in one another.

The rain finally came down hard about 20 minutes later. Great sheets of torrential downpour blowing sideways across the course. I was already safely back in our car, gamely trying to remove my shoes. My legs caked with dirt, my muscles well beyond cramped. It hurt so bad, and felt so satisfying.

The first 30

There’s a few stories to be told about how uneventful the first six hours of the race felt. That’s not to say I didn’t enjoy myself, or marvel at the majesty of late September in Vermont. It was a perfect running day, with temperatures in the 40s and 50s, and ample cloud cover from start to finish.

Given the conditions, the race predictably started out fast. I remained patient and settled into a comfortable groove during the early miles. My aid stations splits were on point, the race began thinning out, and I was in my own universe for several hours.

This was the result of training, pure and simple. The work I did increasing mileage volume during the summer made running 50 miles feel relatively normal. There were no moments of doubt or uncertainty, which meant I had to expend minimal mental energy to remain focused.

Miles 20-30 were fascinating because it was during that point the previous year when I started feeling like I was in over my head. My race became slower, my stomach began feeling unsettled, and my whole body was racked with pain.

This year’s experience was much different. I won’t sit here and say that nothing hurt after 20+ miles, but the pain never felt unmanageable. Hills that forced me into a slow walk the previous year became runnable this time around, and aid stations appeared right on cue whenever I needed them.

I also stayed on top of my nutrition and hydration plan, which made a huge difference late in the race when runners started cramping due to the humidity. I was so dialed in on calories that I made a decision to stop eating during my big push. I knew there was a chance I could bonk, but I didn’t want to risk a stomach blowup. I also felt like I had plenty of energy to finish the job.

These types of tactical race management decisions didn’t happen by accident. They were the result of experience and a year’s worth of growth. Day after day and run after run, when you accept the responsibility of managing your running needs, you can only grow wiser.

When I relayed these stories to Avery after the race, he paused like he does when he’s about to say something profound, and presented me with a merit badge of sorts:

“You’ve hit the point that comes 3-4 years into ultrarunning where you're over the mental hump. It’s an incredible feeling because there’s a lot less unknown. You know you’re going to finish, so everything is now physical. The only question is, how much are you willing to make it hurt?”

A lot more, as it turned out. A whole lot more.

Thank you all for your good thoughts and encouragement throughout this process. Running, Probably will return to its regular twice-a-week publishing schedule with more training advice and running philosophy as we head into the offseason conditioning program. Have a great weekend, everyone.

Congrats on a huge accomplishment! Just being able to see your own year-over-year improvement is great. And this article shows why this newsletter is a valuable resource to a runner of any level. While most of us won't be running ultras, we'll all reach a point in our training and running where "Make It Hurt" is a mantra that can come into play. Even though you are describing it in the context of your 50, things like that apply across the board!

A rich read coming from a rich experience. It must have been a joy writing this as well.